-- Alan Boyle goes over the year in space; National Geographic lists the top ten space discoveries of 2009.

-- Dave Barry's year in review.

-- A recent poll of philosophers indicates that very few believe in God. This contradicts most other reports that theism, and Christianity in particular, are very popular among philosophers today (see here for example). Just Thomism has some links, including a rebuttal.

-- Hollywood pantheism.

-- Is the universe a hologram? It would explain a lot.

-- The social difficulties in being a Christian and (politically) liberal.

-- The ten best long tracking shots ever filmed. Allegedly.

-- The real story behind the Charlie Brown Christmas special.

-- The Vatican praises the Simpsons.

-- Heh. "Only one carry on? No electronics for the first hour of flight? I wish that, just once, some terrorist would try something that you can only foil by upgrading the passengers to first class and giving them free drinks."

-- Very interesting: video games take command of war epics as movies retreat from recent conflicts.

-- Yet more evidence of Saddam Hussein's ties to terrorism.

-- Žižek on the true nature of philosophy.

-- Michael Flynn re-rebuts that atheist website on Christianity and the history of science here and here. The original is here.

Thursday, December 31, 2009

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Yes Virginia, there are flat-earthers

There are some good essays online on the flat earth myth -- the belief that people thought the earth was flat prior to Columbus. I recently linked to this post by M&M, here's another, and here's one James wrote. Humphrey wrote a couple of excellent blogposts on it here and here. The go-to book for all of this is Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians by Jeffrey Burton Russell (you can read a short essay by Russell here) who traces the myth to about 1830 when Washington Irving wrote his "history" of Columbus.

Rather than add to what they wrote, I'd like to address a parallel issue. Once non-Christians started ridiculing Christianity as promoting a flat earth, some Christians sought to defend their faith by ... accepting a flat earth. The most prominent defender, in the mid-19th century, was Samuel Rowbotham, who wrote the book Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe. Rowbotham compiled dozens of evidences supporting his claim that the earth was flat and stationary, such as lighthouses that could be seen from further away than they should if the surface is curved, cannonballs fired straight up from moving platforms (demonstrating that the earth is not moving), etc. To this day there is a flat-earth society which defends this kind of thing. Here is a list of flat-earth literature available to read online. A list of resources by and about flat-earthers is here.

I collect flat-earth literature. It seems to me to be an extreme example of Christians reacting to the conflict myth by letting secularists tell them what to believe, another example being contemporary defenses of geocentrism, something which has gained support among young-earth creationists.

That leads me to my main point: I think young-earth creationism is another example of Christians letting secularists define Christian belief. I don't think it's on the same level as belief in a flat-earth for the simple reason that, throughout history, many of the holiest Christians believed the earth and universe to be young. Nevertheless, the history of young-earth creationism in the last 50 years reveals it to be a reaction rather than a reasoned response, in a very similar fashion as belief in a flat earth was a reaction against the forces of secularism. I submit that this is not an appropriate way for a Christian to act. You can't love the Lord with all your mind if your theology is based on knee-jerk reactions. Moreover, it leads to two deplorable situations: first, as I've already mentioned, where the dictates of one's faith are actually made up by people trying to mock it. As I've mentioned before, I don't think it's wise to let those who deprecate our faith define it for us. Second, it creates a rather large stumbling block for belief in Christianity. If that's what you have to believe in order to be a Christian, then it just obviously fails the smell test.

There are plenty of parallels between young-earth and flat-earth literature. Both make their claim the linchpin to orthodoxy, so that disagreeing with them leads to the denial of central doctrines. Both locate the problems of contemporary society in the rejection of their claim. Both claim that the denial of their claim makes God into an incompetent Creator. Both claim that the denial of their claim is a purely recent phenomenon. Both explicate their claim via bluster and a feigned over-confidence. Etc.

To illustrate that last point, I have a flat-earth book entitled A Reparation: Universal Gravitation a Universal Fake by C. S. DeFord, originally published in 1931, that begins thus:

Methinks he doth protest too much.

(cross-posted at Quodlibeta)

Rather than add to what they wrote, I'd like to address a parallel issue. Once non-Christians started ridiculing Christianity as promoting a flat earth, some Christians sought to defend their faith by ... accepting a flat earth. The most prominent defender, in the mid-19th century, was Samuel Rowbotham, who wrote the book Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe. Rowbotham compiled dozens of evidences supporting his claim that the earth was flat and stationary, such as lighthouses that could be seen from further away than they should if the surface is curved, cannonballs fired straight up from moving platforms (demonstrating that the earth is not moving), etc. To this day there is a flat-earth society which defends this kind of thing. Here is a list of flat-earth literature available to read online. A list of resources by and about flat-earthers is here.

I collect flat-earth literature. It seems to me to be an extreme example of Christians reacting to the conflict myth by letting secularists tell them what to believe, another example being contemporary defenses of geocentrism, something which has gained support among young-earth creationists.

That leads me to my main point: I think young-earth creationism is another example of Christians letting secularists define Christian belief. I don't think it's on the same level as belief in a flat-earth for the simple reason that, throughout history, many of the holiest Christians believed the earth and universe to be young. Nevertheless, the history of young-earth creationism in the last 50 years reveals it to be a reaction rather than a reasoned response, in a very similar fashion as belief in a flat earth was a reaction against the forces of secularism. I submit that this is not an appropriate way for a Christian to act. You can't love the Lord with all your mind if your theology is based on knee-jerk reactions. Moreover, it leads to two deplorable situations: first, as I've already mentioned, where the dictates of one's faith are actually made up by people trying to mock it. As I've mentioned before, I don't think it's wise to let those who deprecate our faith define it for us. Second, it creates a rather large stumbling block for belief in Christianity. If that's what you have to believe in order to be a Christian, then it just obviously fails the smell test.

There are plenty of parallels between young-earth and flat-earth literature. Both make their claim the linchpin to orthodoxy, so that disagreeing with them leads to the denial of central doctrines. Both locate the problems of contemporary society in the rejection of their claim. Both claim that the denial of their claim makes God into an incompetent Creator. Both claim that the denial of their claim is a purely recent phenomenon. Both explicate their claim via bluster and a feigned over-confidence. Etc.

To illustrate that last point, I have a flat-earth book entitled A Reparation: Universal Gravitation a Universal Fake by C. S. DeFord, originally published in 1931, that begins thus:

To me truth is precious. I love it. I embrace it at every opportunity. I do not stop to inquire, Is it popular? ere I embrace it. I inquire only, Is it truth? If my judgment is convinced my conscience approves and my will enforces my acceptance. I want truth for truth's sake, and not for the applaud or approval of men. I would not reject truth because it is unpopular, nor accept error because it is popular. I should rather be right and stand alone than to run with the multitude and be wrong.

Methinks he doth protest too much.

(cross-posted at Quodlibeta)

Labels:

Religion and Science

Saturday, December 26, 2009

It's a small world after all

In order to impress upon Europeans the size of the United States, I've been telling them that the distance between Portland and Boston (the two cities I know best) is about the same as the distance between Brussels and Baghdad. This was based on my estimations while looking at a globe one day. My point was that, when flying from Portland to Boston, you're flying over one country, one culture, one language; while flying from Brussels to Baghdad, on the other hand, you're flying over multiple countries, cultures, and languages.

Well, I just discovered a website that calculates the distance between any two major cities as the crow flies, so I checked it out.

Brussels to Baghdad: 2350 miles (3782 km)

Portland to Boston: 2541 miles (4089 km)

So I've been underestimating it this whole time. I looked for another city to make it more accurate, and came up with this:

Brussels to Tehran: 2542 miles (4092 km)

It kind of freaks me out to know that, right now, I'm as close to Tehran (and closer to Baghdad) than I am to Boston when I'm in Portland. And that's just straight across the States for the most part; if you go from one corner to another (Seattle to Miami, say), it's an even greater distance.

Well, I just discovered a website that calculates the distance between any two major cities as the crow flies, so I checked it out.

Brussels to Baghdad: 2350 miles (3782 km)

Portland to Boston: 2541 miles (4089 km)

So I've been underestimating it this whole time. I looked for another city to make it more accurate, and came up with this:

Brussels to Tehran: 2542 miles (4092 km)

It kind of freaks me out to know that, right now, I'm as close to Tehran (and closer to Baghdad) than I am to Boston when I'm in Portland. And that's just straight across the States for the most part; if you go from one corner to another (Seattle to Miami, say), it's an even greater distance.

Friday, December 25, 2009

Merry Christmas

In the spirit of the season, I present Cur Deus Homo ("Why God Became Man") by Anselm.

Labels:

Books,

Historical Jesus,

Theology

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Update

I've mentioned a couple of times that I'm putting my reading list online (and on the sidebar) at Good Reads. My reason for this is to shame me into getting more done. I've decided to change direction in my studies -- before I was focusing on the problem of epistemic norms, but now I'm approaching the same general idea from a different angle. Part of the reason for this is I have a strong background in the other angle, with plenty of articles already copied in two ridiculously thick notebooks. So it would allow me to start from a place of strength and with a shorter reading list. (I'm being vague on purpose, because it's all very tenuous so far.) I've updated my Good Reads account and the sidebar accordingly. Just in case you were wondering.

Labels:

Maintenance,

Philosophy

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

This is interesting

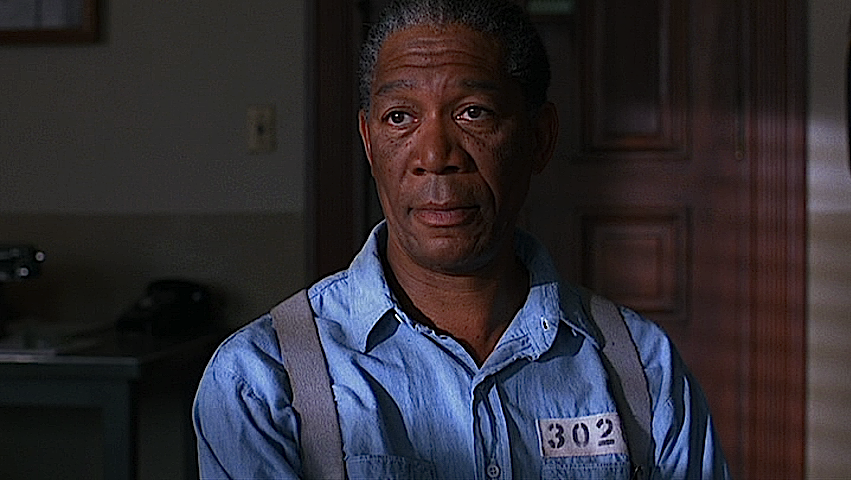

Racial politics in SF movies (and books). Via Matthew Yglesias.

Labels:

Culture and Ethics,

Movies

Saturday, December 19, 2009

Space Linkfest

-- The known universe on video.

-- I've mentioned the MESSENGER spacecraft a couple of times. It will go into orbit around Mercury in 2011, but in the meantime, its swingbys have allowed us to create a global map of Mercury.

-- Saturn's moon Iapetus has one light side and one dark side, a confusing problem that may have just been solved.

-- Here are some awesome pictures from the new Vista telescope. Accompanying article here.

-- And while we're on it, here's an amazing picture of a dying star, showing us what will eventually happen with our own sun.

-- On his blog, Rand Simberg has an update on the Constellation project (the plan to return to the Moon). See also here and here.

-- Elsewhere, Simberg writes about the unveiling of Virgin Galactic's Spaceship Two. Alan Boyle comments as well here.

-- I've mentioned the MESSENGER spacecraft a couple of times. It will go into orbit around Mercury in 2011, but in the meantime, its swingbys have allowed us to create a global map of Mercury.

-- Saturn's moon Iapetus has one light side and one dark side, a confusing problem that may have just been solved.

-- Here are some awesome pictures from the new Vista telescope. Accompanying article here.

-- And while we're on it, here's an amazing picture of a dying star, showing us what will eventually happen with our own sun.

-- On his blog, Rand Simberg has an update on the Constellation project (the plan to return to the Moon). See also here and here.

-- Elsewhere, Simberg writes about the unveiling of Virgin Galactic's Spaceship Two. Alan Boyle comments as well here.

Labels:

Space science

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Urban Philosopher

For one of my theses I came across the writings of philosopher Wilbur Marshall Urban. I was only able to read a few excerpts, but I found them very interesting. I've just discovered that some of his books are available online, so I might get into them soon. Here they are:

Valuation: Its Nature and Laws, Being an Introduction to the General Theory of Value

The Intelligible World: Metaphysics and Value

Fundamentals of Ethics: An Introduction to Moral Philosophy

Humanity and Deity

Here's a quote from one of his books that I couldn't find online, Beyond Realism and Idealism.

A few pages prior to this, he claimed that "The derivative status of mind is the characteristic feature of all forms of naturalism." If this is the case, then this argument -- very similar to C. S. Lewis's Argument from Reason and Alvin Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument against Naturalism -- would seem to apply to "all forms of naturalism." In fact, Urban's statement that "The fact that so many modern minds do not feel difficulties of this sort" is very similar to Lewis's statement "the fact that when you put it to many scientists, far from having an answer, they seem not even to understand what the difficulty is" in his essay "Is Theology Poetry?" in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses. Urban also used a similar argument in chapter 17 of Fundamentals of Ethics.

Valuation: Its Nature and Laws, Being an Introduction to the General Theory of Value

The Intelligible World: Metaphysics and Value

Fundamentals of Ethics: An Introduction to Moral Philosophy

Humanity and Deity

Here's a quote from one of his books that I couldn't find online, Beyond Realism and Idealism.

The main issue then, from which this entire discussion started, and which is involved in the modern identification of realism with naturalism, is the contention that, since reality is prior to knowledge, mind must consequently (italics mine) have a status which is derivative and not pivotal. Why this, consequently, should ever have entered into modern thinking I am at a loss to see. It does not at all follow that, because the principle of being, or the postulate of antecedent reality, is dialectically necessary for an intelligible theory of knowledge, the mind that knows is causally derivative from this antecedent, being conceived as nature in the sense of modern science. This derivative status of mind and knowledge does not follow from the epistemological postulate of realism but is rather an inference, whether rightly or wrongly made, from a specific scientific theory, namely, that of Darwinian evolutionism.

It is natural to want to take the evolutionary picture at its face value, with all that it involves for human knowledge. But we have seen that this naturalistic account does not go very far, and that, when pressed too far, tends to become something 'perverse --' for it, denatures mind and with it the knowledge which it is the minds function to achieve. Such an account makes of the Sermon on the Mount as much of an accident as the Ninth Symphony and of Newton's Principia an even greater anomaly, perhaps, than both.

To the 'transcendentalists' who demur at this perverseness it is pointed out that, after all, it is imply a matter of historical fact that thinking and reasoning man did evolve by natural processes from anthropoid ancestors, a fact not disputed even by those whose deepest feelings are opposed to the admission. But so long as mystery surrounds the manner of the evolution there will always be the refuge of ignorance for the transcendentalists. To me this seems clearly a case of ignoratio elenchi. The issue here is not one of historical fact, although even on this count, the phrases 'historical fact' and 'evolve by natural processes' are both too ambiguous to say whether the above proposition is or is not disputed; in some interpretations it certainly is. The issue is not whether man actually evolved; the question at issue is whether natural processes, in the sense conceived by natural science, can account for mind and intelligence as presupposed by natural science itself. We have here that same logical confusion characteristic of all naturalistic accounts of knowledge. First, various natural sciences are taken as premises for the conclusion that the objects or contents of consciousness occur within the organism as part of the response to stimulation by physical objects other than it. Then we are told that these intra-organic contents have a cognitive function. But how ascribe to these mere contents functions which, by their very nature, they are patently incapable of discharging? This is the pons assinorum which no purely naturalistic account of mind has been able to cross. Or, making use of a figure often employed in this connection, by this supposed 'scientific' account of knowledge, the scientist himself cuts off the very limb upon which he sits. For in thus deriving mind and knowledge from nature, as science conceives it, he must assume that his own account of nature is true. But on his premises, the truth of this account, like that of any other bit of knowledge, is merely the function of the adjustment of the organism to its environment, and thus has no more significance than any other adjustment. Its sole value is its survival value. This entire conception of knowledge refutes itself and is, therefore, widersinnig. The fact that so many modern minds do not feel difficulties of this sort is one of the things I have never been able to understand. I can only surmise that our devotion to so-called empiricism has robbed us of all sense of logicality, or what I should call the finer inner harmonies of thought -- in short, the sense for philosophical intelligibility.

As to the transcendentalists, their belief in the transcendental character of mind is not the refuge of ignorance, but rather the result of their realization of the peculiarly vicious circle involved in all naturalistic accounts of knowledge. It is not their feelings that are outraged but their intellects.

A few pages prior to this, he claimed that "The derivative status of mind is the characteristic feature of all forms of naturalism." If this is the case, then this argument -- very similar to C. S. Lewis's Argument from Reason and Alvin Plantinga's Evolutionary Argument against Naturalism -- would seem to apply to "all forms of naturalism." In fact, Urban's statement that "The fact that so many modern minds do not feel difficulties of this sort" is very similar to Lewis's statement "the fact that when you put it to many scientists, far from having an answer, they seem not even to understand what the difficulty is" in his essay "Is Theology Poetry?" in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses. Urban also used a similar argument in chapter 17 of Fundamentals of Ethics.

Labels:

Books,

Philosophers,

Philosophy,

Religion and Science

Sunday, December 13, 2009

Some Issues in NT Historiography, part 3

It is sometimes asserted by radical NT scholars that the early church was constantly inventing stories about Jesus, and that the gospel authors were falsifying sayings of Jesus in order to meet the needs of the church later. But if this were true, then why are there so many statements by Jesus that were irrelevant to the later church? His reluctance to help people other than "the lost sheep of Israel" (Matthew 15:21-28) would not have been something the church made up since by the AD 50s there were many non-Jewish (Gentile) Christians. Moreover, there are many issues the church struggled with, such as whether Gentiles should be circumcised. If sayings of Jesus were being invented to serve the needs of the church, issues like this would have been addressed. But they aren’t.

The main assertion here is that since the gospels were written with the intent of converting people, the authors must have considered historical accuracy secondary, if not totally irrelevant. Of course, there is a kernel of truth here: people often have ulterior motives. We should certainly look closer to see if their religious motivation caused the gospel authors to distort history, but we shouldn’t use this as an excuse to just dismiss the gospels out of hand. This would entirely obviate the job of the historian, which is to sift through documents and determine what’s historically accurate and what’s not. If the presence of motives allowed us to dismiss a document without any further analysis, there would be nothing for the historian to do. But obviously this is ridiculous; this objection amounts to an all or nothing scenario where a document is either pure history or pure fiction.

The reason this is ridiculous is that all ancient histories were written with some ideological motive, be it religious or political. Indeed, it’s impossible to write a purely unbiased history. Moreover if what the gospels report on actually happened, we should expect the authors to go to great extremes to tell others about it with great zeal. In other words, we should expect them to do exactly what they did.

Another problem with this assertion is that there were many eyewitnesses of Jesus’ ministry, some of whom would have survived at least through the first decade of the second century. And since Christianity was controversial, these people would be considered to be able to speak authoritatively about Jesus and would be sought out to determine whether certain things about him were true or not. As F. F. Bruce writes:

The fact that Christianity was centrally located in Jerusalem where many of the events took place makes the number of eyewitnesses here absolutely huge. This makes it very difficult to claim that gospels could be written which were not historically accurate but which would then go unchallenged by the hostile eyewitnesses (who wanted to destroy Christianity), not to mention the Christian eyewitnesses who were being tortured and killed for their belief and therefore had a stake in whether the gospels were accurate or not.

Moreover, there is very strong historical evidence demonstrating that the gospel authors were sincerely trying to record historical events accurately; such things as harmful details -- things that would not help, and would certainly hurt, attempts to convince people in first century Palestine that Christianity was true. For example, in all four gospels, women are the first people to find Jesus’ tomb empty. What is amazing about this is that women were believed to be hopeless gossips in first century Palestine and, as such, their testimony was considered completely worthless. Given this social and cultural attitude, what possible motive could the gospel authors have had for including this, other than that’s what actually happened, and they felt obliged to be truthful about it?

Other examples of this would include Peter’s denying that he even knew Jesus three times, recorded in all four gospels (Matthew 26:69-75; Mark 14:66-72; Luke 22:54-62; John 18:15-18, 25-27). Peter was one of the main evangelists, the last thing the Christians would want people to think is that he wasn’t trustworthy. This is true of all the followers of Jesus; they’re represented in the gospels as being cowards who just weren’t that bright. They were constantly misunderstanding Jesus, failing to trust him, and following their own selfish motives rather than God. These were the same people who were the leaders of the early church and trying to convince people that Christianity was true. They would never have disparaged their own characters like this unless these things actually happened and they felt obliged to be truthful about it.

Another type of unusual detail we find in the gospels are those that would have been, for some reason or another, difficult for people to understand. Gregory Boyd writes in Jesus Under Siege:

But this is also quite common in the gospels: events that have enormous theological significance are detailed but not explained (John 20:17, for example). If the gospel authors were making up stories about Jesus they wouldn’t leave such important threads hanging. But if they were trying to record accurate history first and theological reflection second, this is exactly what we should expect.

Update (15 Feb 2010): See also part 1, part 2, part 4, and part 5.

The main assertion here is that since the gospels were written with the intent of converting people, the authors must have considered historical accuracy secondary, if not totally irrelevant. Of course, there is a kernel of truth here: people often have ulterior motives. We should certainly look closer to see if their religious motivation caused the gospel authors to distort history, but we shouldn’t use this as an excuse to just dismiss the gospels out of hand. This would entirely obviate the job of the historian, which is to sift through documents and determine what’s historically accurate and what’s not. If the presence of motives allowed us to dismiss a document without any further analysis, there would be nothing for the historian to do. But obviously this is ridiculous; this objection amounts to an all or nothing scenario where a document is either pure history or pure fiction.

The reason this is ridiculous is that all ancient histories were written with some ideological motive, be it religious or political. Indeed, it’s impossible to write a purely unbiased history. Moreover if what the gospels report on actually happened, we should expect the authors to go to great extremes to tell others about it with great zeal. In other words, we should expect them to do exactly what they did.

Another problem with this assertion is that there were many eyewitnesses of Jesus’ ministry, some of whom would have survived at least through the first decade of the second century. And since Christianity was controversial, these people would be considered to be able to speak authoritatively about Jesus and would be sought out to determine whether certain things about him were true or not. As F. F. Bruce writes:

And it was not only friendly eyewitnesses that the early preachers had to reckon with; there were others less well disposed who were also conversant with the main facts of the ministry and death of Jesus. The disciples could not afford to risk inaccuracies (not to speak of wilful manipulation of the facts), which would at once be exposed by those who would be only too glad to do so. On the contrary, one of the strong points in the original apostolic preaching is the confident appeal to the knowledge of the hearers; they not only said, ‘We are witnesses of these things,’ but also, ‘As you yourselves also know’ (Acts 2:22 [also 26:26]). Had there been any tendency to depart from the facts in any material respect, the possible presence of hostile witnesses in the audience would have served as a further corrective.

The fact that Christianity was centrally located in Jerusalem where many of the events took place makes the number of eyewitnesses here absolutely huge. This makes it very difficult to claim that gospels could be written which were not historically accurate but which would then go unchallenged by the hostile eyewitnesses (who wanted to destroy Christianity), not to mention the Christian eyewitnesses who were being tortured and killed for their belief and therefore had a stake in whether the gospels were accurate or not.

Moreover, there is very strong historical evidence demonstrating that the gospel authors were sincerely trying to record historical events accurately; such things as harmful details -- things that would not help, and would certainly hurt, attempts to convince people in first century Palestine that Christianity was true. For example, in all four gospels, women are the first people to find Jesus’ tomb empty. What is amazing about this is that women were believed to be hopeless gossips in first century Palestine and, as such, their testimony was considered completely worthless. Given this social and cultural attitude, what possible motive could the gospel authors have had for including this, other than that’s what actually happened, and they felt obliged to be truthful about it?

Other examples of this would include Peter’s denying that he even knew Jesus three times, recorded in all four gospels (Matthew 26:69-75; Mark 14:66-72; Luke 22:54-62; John 18:15-18, 25-27). Peter was one of the main evangelists, the last thing the Christians would want people to think is that he wasn’t trustworthy. This is true of all the followers of Jesus; they’re represented in the gospels as being cowards who just weren’t that bright. They were constantly misunderstanding Jesus, failing to trust him, and following their own selfish motives rather than God. These were the same people who were the leaders of the early church and trying to convince people that Christianity was true. They would never have disparaged their own characters like this unless these things actually happened and they felt obliged to be truthful about it.

Another type of unusual detail we find in the gospels are those that would have been, for some reason or another, difficult for people to understand. Gregory Boyd writes in Jesus Under Siege:

For example, Jesus’ parable about the farmer sowing seed which falls on rocky, shallow, and good soil, only makes sense in a Palestinian environment where seed was sowed before the ground was plowed (Mark 4:1-8 and Luke 8:5-8). Elsewhere throughout the Roman Empire the practice was to plow the ground first. Such accurate detail suggests that the teachings of Jesus were passed on in their original form, even in contexts in which the form of His teaching wouldn’t have made immediate sense. ... In just the same way, there is absolutely no discernible motive -- aside from the motive to "tell it like it really happened" -- for why the Gospels include the unusual detail that Jesus, while dying on the Cross, cried out, "My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?" If the Gospel writers’ driving purpose was to portray Christ as the Messiah ("anointed one") and as the Son of God, this was the last thing in the world they would ever want to include in their narrative. They certainly wouldn’t make it up on their own!

But this is also quite common in the gospels: events that have enormous theological significance are detailed but not explained (John 20:17, for example). If the gospel authors were making up stories about Jesus they wouldn’t leave such important threads hanging. But if they were trying to record accurate history first and theological reflection second, this is exactly what we should expect.

Update (15 Feb 2010): See also part 1, part 2, part 4, and part 5.

Labels:

Historical Jesus

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Craig vs. Spong

I recently listened to a debate between William Lane Craig and John Shelby Spong on the historical Jesus (this was an actual debate, unlike the presentation and response Craig had with Dennett). You can listen to it here. Craig argued that Spong is so insulated that he doesn't know what scholars outside of his small circle actually say. He points out that a survey of NT scholarship of the last few decades indicates that three-fourths of the scholars writing on the subject accept the historicity of Jesus' empty tomb, and almost universally accept his post-mortem appearances as historically demonstrable. Moreover, most scholars today recognize that the four gospels are written as historical writing, specifically in the genre of ancient biography -- not myth, not legend, not allegory, not midrash (as Spong claims). Spong seems genuinely puzzled by this. It reminds me of something N. T. Wright wrote of Spong in Who Was Jesus?

A moment in the debate that particularly struck me was when Spong related how Carl Sagan had once approached him and said something to the effect of, if Jesus had ascended away from the surface of the earth at the speed of light, he'd still be in the Milky Way galaxy. This is essentially the claim that the Ascension was predicated on a local heaven just above the clouds and thus that the ancients and medievals didn't know the universe is incomprehensibly large, something I showed to be false here.

The fact that Spong thinks this is a good or original point further demonstrates how insulated he is. The South England Legendary, written in the 13th century, says something similar. C. S. Lewis writes in The Discarded Image, that the Legendary is "better evidence than any learned production could be for the Model as it existed in the imagination of ordinary people. We are there told that if a man could travel upwards at the rate of ‘forty mile and yet som del mo’ a day, he still would not have reached the Stellatum (‘the highest heven that ye alday seeth’) in 8000 years." Since this was common knowledge several hundred years before it occurred to Sagan or Spong, I can't get too excited about their "insight", much less their claim that it threatens traditional Christianity -- a point that the South England Legendary somehow misses.

(cross-posted at Quodlibeta)

What is central is that Spong apparently does not know what 'midrash' actually is. The 'genre' of writing to which he makes such confident appeal is nothing at all like he says it is. There is such a thing as 'midrash'; scholars have been studying it, discussing it, and analysing it, for years. Spong seems to be unaware of the most basic results of this study. He has grabbed the word out of the air, much as Barbara Thiering grabbed the idea of 'pesher' exegesis, and to much the same effect. He misunderstands the method itself, and uses this bent tool to make the gospels mean what he wants instead of what they say.

...

We may briefly indicate the ways in which genuine 'midrash' differs drastically from anything that we find in the gospels.

First, midrash proper consists of a commentary on an actual biblical text. It is not simply a fanciful retelling, but a careful discussion in which the original text itself remains clearly in focus. It is obvious that the gospels do not read in any way like this.

Second, real midrash is 'tightly controlled and argued'. This is in direct opposition to Spong's idea of it, according to which (p. 184) 'once you enter the midrash tradition, the imagination is freed to roam and to speculate'. This statement tells us a good deal about Spong's own method of doing history, and nothing whatever about midrash. The use made of the Old Testament in the early chapters of Luke, to take an example, is certainly not midrash; neither is it roaming or speculative imagination.

Third, real midrash is a commentary precisely on Scripture. Goulder's theories, on which Spong professes to rely quite closely, suggest that Luke and Matthew were providing midrash on Mark. It is, however, fantastically unlikely that either of them would apply to Mark a technique developed for commenting on ancient Scripture.

Fourth, midrash never included the invention of stories which were clearly seen as non-literal in intent, and merely designed to evoke awe and wonder. It was no part of Jewish midrash, or any other Jewish writing-genre in the first century, to invent all kinds of new episodes about recent history in order to advance the claim that the Scriptures had been fulfilled. It is one of the salient characteristics of Jewish literature throughout the New Testament period that, even though novelistic elements could creep in to books like Jubilees, the basic emphasis remains on that which happened within history.

A moment in the debate that particularly struck me was when Spong related how Carl Sagan had once approached him and said something to the effect of, if Jesus had ascended away from the surface of the earth at the speed of light, he'd still be in the Milky Way galaxy. This is essentially the claim that the Ascension was predicated on a local heaven just above the clouds and thus that the ancients and medievals didn't know the universe is incomprehensibly large, something I showed to be false here.

The fact that Spong thinks this is a good or original point further demonstrates how insulated he is. The South England Legendary, written in the 13th century, says something similar. C. S. Lewis writes in The Discarded Image, that the Legendary is "better evidence than any learned production could be for the Model as it existed in the imagination of ordinary people. We are there told that if a man could travel upwards at the rate of ‘forty mile and yet som del mo’ a day, he still would not have reached the Stellatum (‘the highest heven that ye alday seeth’) in 8000 years." Since this was common knowledge several hundred years before it occurred to Sagan or Spong, I can't get too excited about their "insight", much less their claim that it threatens traditional Christianity -- a point that the South England Legendary somehow misses.

(cross-posted at Quodlibeta)

Broad Christianity

Here's an interesting quote on the nature of Christianity by philosopher C. D. Broad.

Labels:

Historical Jesus,

Philosophy,

Theology

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Science Linkfest

-- "Virgin Galactic Poised to Unveil Suborbital Space Liner". So cool.

-- "Amputee able to move robotic hand with his mind". To reitereate: So cool.

-- Here are some interesting photos of new undersea cables connecting Europe and the States, along with how they've developed.

-- Please, no jokes. Uranus's almost 90 degree tilt may be the result of a large moon that is no longer there. It's just a theory; there's no evidence for the moon other than its explanatory power in accounting for the tilt (which is not insignificant). And if I may propose the absurd connection of the day, remember that Earth once had a much thicker atmosphere until it was struck by a large Mars-sized object which blew most of the atmosphere away and gave us our Moon. It's because of this collision that Earth is able to support life. Now we suspect something large used to orbit Uranus but isn't there anymore. Coincidence? Almost certainly.

-- For anyone who's interested, I compiled a linkfest on Climategate, a.k.a. Climaquiddick, here. It's about a week old at this point, so more recent articles aren't included. Also, bear in mind that most of the links are from the political right, so it's basically criticism of the controversy without much in the way of exculpatory arguments.

-- "Amputee able to move robotic hand with his mind". To reitereate: So cool.

-- Here are some interesting photos of new undersea cables connecting Europe and the States, along with how they've developed.

Although there have been undersea cables connecting Britain and the US since the late 19th century, until 1956 these could only handle Morse code.

Data capacity of a single cable has increased 80,000 times in just 20 years.

-- Please, no jokes. Uranus's almost 90 degree tilt may be the result of a large moon that is no longer there. It's just a theory; there's no evidence for the moon other than its explanatory power in accounting for the tilt (which is not insignificant). And if I may propose the absurd connection of the day, remember that Earth once had a much thicker atmosphere until it was struck by a large Mars-sized object which blew most of the atmosphere away and gave us our Moon. It's because of this collision that Earth is able to support life. Now we suspect something large used to orbit Uranus but isn't there anymore. Coincidence? Almost certainly.

-- For anyone who's interested, I compiled a linkfest on Climategate, a.k.a. Climaquiddick, here. It's about a week old at this point, so more recent articles aren't included. Also, bear in mind that most of the links are from the political right, so it's basically criticism of the controversy without much in the way of exculpatory arguments.

Labels:

Science,

Space science

Carnivals

I've expanded the list of Other Blogrolls on the sidebar to include Carnivals. These are summaries or updates of some broad subject done regularly, but hosted by a different blog each time. The two I've added are the Carnival of Space, done every week, and the Philosophers' Carnival done every three weeks. The links take you to the home page which links to each of the individual hosts. I'll probably add more as time goes by.

Update: Only a few minutes later and I've already added the Patristics Carnival.

Update: Only a few minutes later and I've already added the Patristics Carnival.

Labels:

Maintenance,

Philosophy,

Space science

Friday, December 4, 2009

One More Book

From this account it looks like I'm going to have to read The Counter-Revolution of Science by F. A. Hayek.

Labels:

Books,

Philosophy,

Science

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Moosik

Over a year ago I wrote about my favorite piece of music: the Meditation from Massenet's Thaïs. I just heard another lovely version of it, Yo-yo Ma on cello with piano accompaniment.

Another favorite piece is "Tu se' morta" from Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo. This song is Orpheus lamenting that his beloved Eurydice is dead, and vowing to go to the underworld to bring her back. It ends with him singing "Goodbye world, goodbye sky; and sun, goodbye." It's just heartbreaking. You can hear it here. Monteverdi kind of straddles the Renaissance and Baroque eras, similar to how Beethoven straddles Viennese Classicism and Romanticism.

I'm linking to them because I can't embed them. To make up for this, and to split the difference between the two, here's J. S. Bach's Partita for flute in A minor. I pretty much love everything by Bach, but I think he's at his best when writing for solo instruments.

Another favorite piece is "Tu se' morta" from Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo. This song is Orpheus lamenting that his beloved Eurydice is dead, and vowing to go to the underworld to bring her back. It ends with him singing "Goodbye world, goodbye sky; and sun, goodbye." It's just heartbreaking. You can hear it here. Monteverdi kind of straddles the Renaissance and Baroque eras, similar to how Beethoven straddles Viennese Classicism and Romanticism.

I'm linking to them because I can't embed them. To make up for this, and to split the difference between the two, here's J. S. Bach's Partita for flute in A minor. I pretty much love everything by Bach, but I think he's at his best when writing for solo instruments.

Labels:

Music

Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Prayer Request

I don't usually blog about personal stuff here, but I would like to make a few prayer requests.

1. First and foremost, my wife is seven months pregnant and for the last couple of months or so she has been experiencing crippling head pain. They did an MRI and didn't find any problems. She experienced headaches when she was pregnant with our first child too, but not this bad. Because she's pregnant she can't take anything but Tylenol (Paracetamol), and it simply doesn't do anything. We might have to take her to the emergency room, but I don't think they'll be able to do anything for her. This is the primary thing, it's what motivated me to write this post in the first place.

2. Finances. My wife and I are both Ph.D. students living abroad and it's enormously difficult to earn enough money to make ends meet. What's most frustrating about this is that my mother passed away in June and left us some money. This came right at a moment when we had no other income, so we've been using the inheritance to pay our rent. I hate doing this. We could see it as God providing us with a windfall of money at just the moment when our usual sources dried up, but it just kills me that this means blowing through the money my mother left me.

3. This is a more general concern, but just pray for my wife and I to be good parents to our son and to our child who's on the way. With the studies and the sporadic employment, it makes it easy to lose track of what's important.

(Update)

4. Our studies. Right now it's nearly impossible for either of us to get any serious studying done. I should be spending 40-60 hours a week reading and I can't even come close to it. We're both older students, so it's very important that we finish our Ph.D.s as quickly as possible if we still want to be employable.

(Update)

5. We're also going through some trials that I won't go into because of their personal nature, but which are very distressing. Prayers would be appreciated.

1. First and foremost, my wife is seven months pregnant and for the last couple of months or so she has been experiencing crippling head pain. They did an MRI and didn't find any problems. She experienced headaches when she was pregnant with our first child too, but not this bad. Because she's pregnant she can't take anything but Tylenol (Paracetamol), and it simply doesn't do anything. We might have to take her to the emergency room, but I don't think they'll be able to do anything for her. This is the primary thing, it's what motivated me to write this post in the first place.

2. Finances. My wife and I are both Ph.D. students living abroad and it's enormously difficult to earn enough money to make ends meet. What's most frustrating about this is that my mother passed away in June and left us some money. This came right at a moment when we had no other income, so we've been using the inheritance to pay our rent. I hate doing this. We could see it as God providing us with a windfall of money at just the moment when our usual sources dried up, but it just kills me that this means blowing through the money my mother left me.

3. This is a more general concern, but just pray for my wife and I to be good parents to our son and to our child who's on the way. With the studies and the sporadic employment, it makes it easy to lose track of what's important.

(Update)

4. Our studies. Right now it's nearly impossible for either of us to get any serious studying done. I should be spending 40-60 hours a week reading and I can't even come close to it. We're both older students, so it's very important that we finish our Ph.D.s as quickly as possible if we still want to be employable.

(Update)

5. We're also going through some trials that I won't go into because of their personal nature, but which are very distressing. Prayers would be appreciated.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)